Introduction

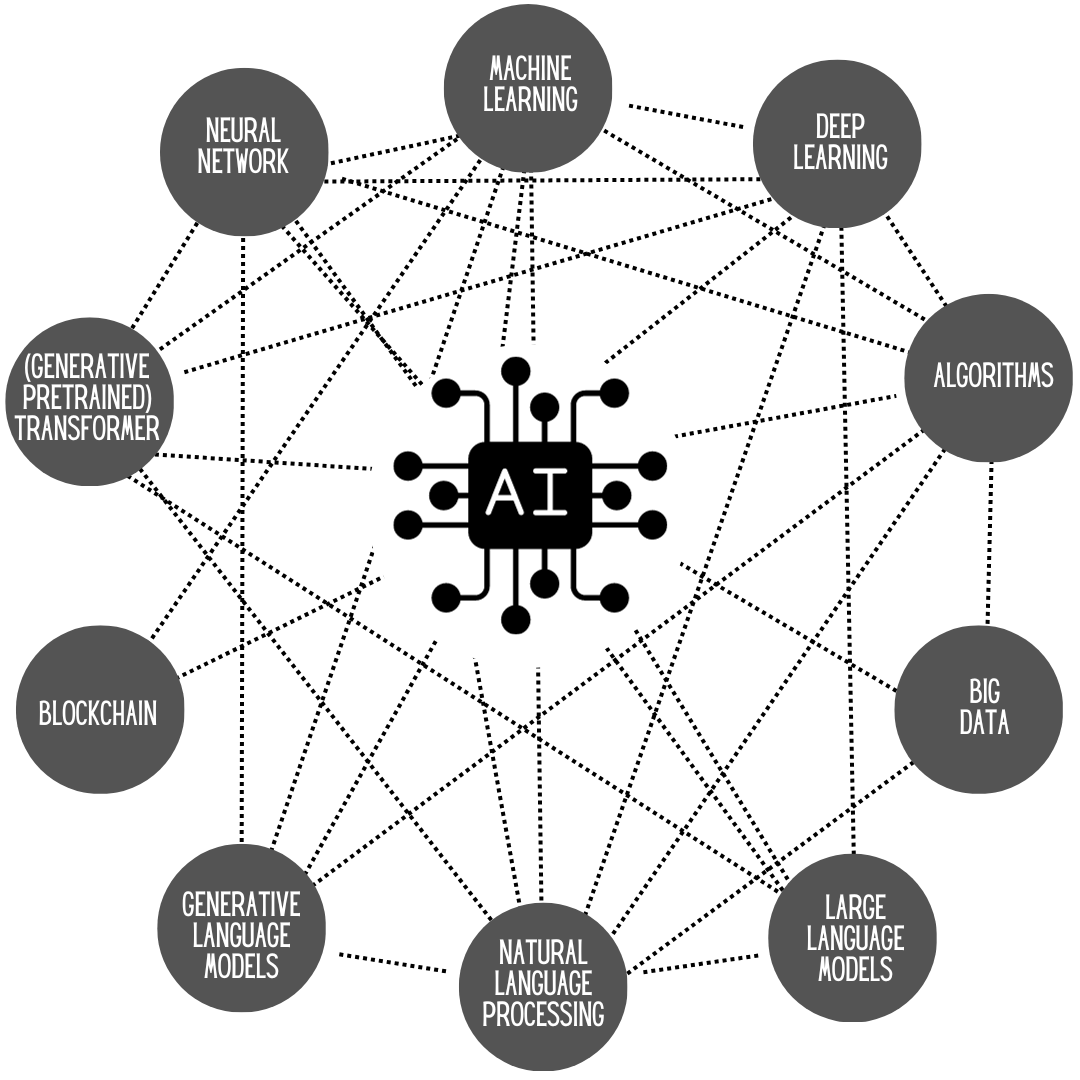

We are living in a time when the pace of technology moves so quickly that all sectors of society are in constant flux, adjusting to the changes that continually roll out from technological innovators. To situate the pace of technological transformation, we need only consider that in 1965, microchip engineer Gordon Moore, cofounder of the Intel Corporation, famously observed that the number of components on a microchip were doubling every year, which resulted in technological advancements continually improving while simultaneously becoming more affordable. Shalf and Leeland summarized Moore’s Law as the prediction “that this trend, driven by economic considerations of cost and yield, would continue for at least a decade, although later the integration pace was moderated to doubling approximately every 18 months” (2018, p. 14). This already incredible rate of change has brought forth new challenges and considerations to countries and cultures everywhere. Modern humans are inundated with information, news, communication, and a wide array of other notifications from all manner of devices. With this ease of information flow and data consumption, new challenges have arisen, not the least of which is the concept of algorithmic personalization, also referred to as algorithmic governance, or algocracy (Aneesh, 2006). Defined as “the probability that a set of coded instructions in heterogeneous input-output computing systems will be able to render decisions without human intervention and/or structure the possible field of action by harnessing specific data” (Issar & Aneesh, 2022, p. 3), algorithmic governance exists, behind the scenes, and largely unnoticed in many of our digital interactions. Notwithstanding the fact that “algorithms are a powerful if largely unnoticed social presence” (Beer, 2017, p. 2), they appear to not be a topic of concern to many people beyond those who work in technology. Regardless of the lack of popular concern, the algorithms that operate in the background of the technologies we engage with are a powerful social influence, holding the potential to control the flow of information (Alkhatib & Bernstein, 2019; Harris, 2022; Hobbs, 2020), the credibility of the information (Connolly, 2023; Blake-Turner, 2020; Harris, 2022; Hobbs, 2020; Issar & Aneesh, 2022), the surveillance of the people (Issar & Aneesh, 2022), and the visibility of the people (Bucher, 2012; Hoadley, 2017) who use the technology. The fact that “authority is increasingly expressed algorithmically” (Pasquale, 2015, p. 7-8) should present concerns to learning scientists, as hegemonic processes, epistemic stability, obscured voices, and human agency sit at the core of the Learning Sciences, as it aims to “productively address the most compelling issues of learning today” (Philip & Sengupta, 2021, p. 331). Though some authors use the term ‘algorithmic personalization’, to continue to underscore the power wielded by the ubiquitous algorithms, I will use the term algorithmic governance throughout this paper.

The first topic to address is that of the flow of information as “today, algorithmic personalization is present nearly every time users use the internet, shaping the offerings displayed for information, entertainment, and persuasion” (Hobbs, 2020, p. 523). This brings forward the obvious epistemic question: who decides which items are brought to the user’s attention, and equally importantly, what is not brought to the user’s attention? The lack of transparency of the algorithms (Alkhatib & Bernstein, 2019, p. 3) coupled with the fact that even those who create algorithms cannot fully understand the machine-learning mechanisms by which the decisions are reached (Hobbs, 2020; Rainie & Anderson, 2017), creates a perplexing and nebulous problem: we don’t actually know who controls our flow of digital information. This creates an epistemic fracture, in the sense that the manner in which information is delivered to the user is unknown, and the accuracy of the information being delivered may or may not be true. Societies across the world are facing intense social and political polarization (Conway, 2020, p. 3), and the role that the algorithms play in reinforcing problematic beliefs is complicit in the creation of this fragmentation.

A quick glance at the creators and CEOs of a few of the major technology companies (Google [Alphabet] Facebook [Meta], Twitter [X] and Amazon) suggests a possibility that white males have dominated the industry to date, and it would be illogical to assume that the algorithms, written by white, western, colonial settlers, would be void of any human bias. Hobbs summed it up succinctly saying that “algorithms are created by people whose own biases may be embodied in the code they write” (2020, p. 524). This assumption demands attention, as the potential to continue the hegemonic control of information exists within the algorithms. Considering the colonial mindset upon which Canada and the United States were founded, asking questions about who is determining the content we consume digitally is imperative; our history is one of enslavement and White dominance as opposed to one of collaboration and equality, and this legacy may now play a silent, covert role in our digital society today. We need only look to our recent history to see that our history in print books served to perpetuate the domination of white culture, which King and Simmons sum up saying “in many traditional history textbooks, history moves through a paradigm that is historically important to the dominant White culture (2018, p. 110). It does not seem a leap in logic to assume that at least some of the algorithms underlying the digital technologies we use on a daily basis may be complicit, as textbooks have been, in focusing the attention of the user back onto a White gaze. Marin’s statement about Western assumptions that they “often tacitly work their way into research on human learning and development and the design of learning environments” (2020, p. 281) underscores not only the possibility, but indeed the likelihood that the oppression is ongoing today.

This suspicion of control is compounded by occasional changes that are actually visible. An example of this is Elon Musk arbitrarily changing the information flow on Twitter, including enforcing users to have a Twitter login to view tweets, then silently removing this limiting requirement, to instead limit the number of tweets a person would be permitted to read in a given day (Warzel, 2023). To compound the dubious nature of these changes, Musk is a “self-professed free-speech ‘absolutist’” (Warzel, 2023), a statement that serves not to alleviate, but rather to underscore reasons to be suspicious of his platform and its algorithm, as some of his statements that he has personally made ‘freely’, have revealed him to be duplicitous (Farrow, 2023). It is worthwhile, however to note that many users have taken a break from this platform, have left it entirely, or do not see themselves being active on that platform a year down the line (Dinesh & OdabaŞ, 2023) since Musk’s takeover, and ongoing rebranding and changing of the platform. Beyond the fact that when the majority of users signed up for Twitter, these restrictions (as well as the eased restrictions) were not what the users signed up for or agreed to; it should be noted that when Obar and Oeldorf-Hirsch updated the academic literature regarding people’s reading of the user agreements, the previous research was supported, and their summary revealed that “individuals often ignore privacy and TOS policies for social networking services” (2020, p. 142). So, although the user experience on Twitter has changed since Musk’s acquisition, it should not be suggested that users would not have agreed to these terms and conditions, as they would not likely have read these terms.

A second major consideration as it pertains to algorithmic governance is the concept of credibility of the information we encounter online. We have already established that the flow of information is controlled, shaped, eased, and released algorithmically. These same algorithms are also responsible for the broad distribution of the barrage of disinformation and fake news in recent years. Misinformation is content that circulates online containing untrue information, but the intention behind it is, at least in some cases innocent, in that the person sharing it believed it to be real. Altay et al. defined misinformation as being “in its broadest sense, that is, as an umbrella term encompassing all forms of false or misleading information regardless of the intent behind it” (2023, p. 2). Fake news, on the other hand, has a more specific definition as it is deliberately untrue. Springboarding from the definition Rini (2017) proposed for fake news, Blake-Turner defined fake news as

one that purports to describe events in the real world. Typically by mimicking the conventions of traditional media reportage, yet is [not justiciable believed by its creators to be significantly true], and is transmitted [by them] with the two goals of being widely re-transmitted and of deceiving at least some of its audience” (2020, p. 2).

Politicians and leaders regularly engage in the creation and promotion of fake news in their campaigns, news releases, and press conferences in their quest to maintain their voting base, and whenever possible to increase it. This fake news is then shared and redistributed by followers of the political party responsible for the fake news, it is run through the algorithms that govern information, and is then delivered to the people who are most likely to believe it.

Lying is by no means a new skill in the world of politics. From the beginnings of democracy, impressing the voter in some capacity has been important to gaining or retaining power. “The importance of the political domain ensures that some parties have good pragmatic reason to fake such content – a point illustrated b y the long history of misleading claims and advertisements in politics” (Harris, 2022, p. 83). The newcomer in this is the ability of the common person to create content that appears to be true. In the past, news and information was communicated through television, newspapers, magazines, and books; all of which involved an editor who would carefully read through all manuscripts and determine their publication value. Today, anyone with a computer, some simple photo editing apps, and a commitment to an idea can create content that not only seems real, it is entirely believable. Our older generations have lived the majority of their lives in a time when published material had already been vetted, and to them, published materials were factual. Now they, along with the younger generations, are faced every day with realistic fakes that challenge everyone to question the truth of practically everything encountered online. Places that were once able to deliver accurate and factual knowledge are now deceptive, and at times are even difficult to fact check.

Deepfakes are a newcomer to the world of publishing that usher in an even deeper level of falsehoods, obscuring of facts, and incredibly inauthentic yet lifelike video footage. “The term ‘deepfake’ is most commonly used to refer to videos generated through deep learning processes that allow for an individual’s likeness to be superimposed onto a figure in an existing video” (Harris, 2022, p. 83). Our epistemic environment has already been compromised by the prevalence of untrue words typed on the screen, along with compellingly falsified photos and images, and now we are facing the corruption of that which was previously seen to be the “smoking gun” of truth; the video evidence. Harris also informed that at the time of his writing, a mere year ago, deepfakes remained relatively unconvincing; with the sudden advent of AI, deepfakes have already grown increasingly more realistic.

Misinformation and fake news create epistemic problems in modern society. Blake-Turner defined an epistemic environment as including “various things a member of the community is in a position to know, or at least rationally believe, about the environment itself” (2020, p. 10). The key words in the definition: rationally believe, underscore how the existence of fake news and deepfake technology create tensions between what is fact, and what is believed to be fact. At the time of this writing, the former American President has been indicted four times, in four different states, facing 91 felony (Baker, 2023) charges, almost all of which relate to lying, misinformation, and ultimately turning those lies into action to attempt to overturn the results of the 2020 federal election. In an illustration of the severity of the epistemic problem, those lies and his disinformation resulted in an attack on the U.S. Capitol on January 6, 2021, they have resulted in hundreds of people being sentenced to jail time for their participation in that riot, police have been beaten and killed, and the threats of violence and riots continue from this former president. Blake-Turner helps make sense of the manner in which these events came to pass: “the more fake news stories that are in circulation, the more alternatives are made salient and thereby relevant – alternatives that agents must be in a position to rule out (2020, p. 11). The onslaught of lies, misinformation and political propaganda have created an environment where many people have struggled to find the truth in the midst of all this chaos and deceit.

Surveillance of the people

Another crucial element of the algorithms that live in our midst is the subtle, yet ongoing surveillance of the people who use the technology. As users of networked technology, we should all be aware that surveillance could be occurring, but the extent to which it is really happening should be of concern. “While the problem of surveillance has often been equated with the loss of privacy, its effects are wider as it reflects a form of asymmetrical dominance where the party at the receiving end may not know that they are under surveillance” (Issar & Aneesh, 2021, p. 7). Foucault described surveillance through what he termed panopticism, describing an architectural arrangement whereby people were always being watched. Arguably, the pantopticon has been created virtually via the digital trails we create when we utilize networked technologies. In 2016 the British firm Cambridge Analytica reported having 4,000 data points on each voter in the United States; data which included some voluntarily given data, but also much subversive data, including data gathered from Facebook, loyalty cards, gym memberships and other traceable data (Brannelly, 2016). While these numbers are shocking, it is made worse by the fact that this data was sold, and then used by the Republican party to target and influence undecided voters to vote for Donald Trump in the 2016 election. This aligns with the statement made by Issar and Aneesh that “while the problem of surveillance has often been equated with the loss of privacy, its effects are wider as it reflects a form of asymmetrical dominance where the party at the receiving end may not know that they are under surveillance (2021, p. 7). The American voters were oblivious to the fact that their data was being collected in the manner that it was, that their personal data was being amassed and collected into one neat package, and that this package was being sold for the purposes of manipulating emotions to achieve the political goal of one party. Ironically, as his court dates approach, even the duplicitous former president of the United States could not escape surveillance; his movements, messages, conversations, and other interactions were also recorded, and though he continues to lie about his actions, and manipulate some public perception of some of his deeds, he has been unable to exert enough control to not, eventually, be exposed. The ongoing misinformation campaign, however, and the algorithmic governance will continue to provide his supporters with images, words, articles and ideas that uphold their damaged, and inaccurate beliefs.

In the model of surveillance, everyone is being watched, everyone is visible. Bucher stated that “surveillance thus signifies a state of permanent visibility” (2012, p. 1170), however, “concerns about the privacy impact of new technologies are nothing new” (Joinson et al., 2011 p. 33). Within networks, and social media there exists a privacy paradox whereby when individuals are asked about privacy, “individuals appear to value privacy, but when behaviors are examined, individual actions suggest that privacy is not a priority” (Norberg et al., 2007; Obar & Oeldorf-Hirsch, 2022, p. 142). After hastily clicking “accept” to the user agreement, we navigate through the internet, viewing personalized advertisements and “information” nuggets that align with our personal interests, and we grow increasingly oblivious to the fact that this “algorithmic personalization is part of what is termed surveillance capitalism, “the practice of translating human experience into data that can be used to make predictions about behavior” (Hobbs, 2020, p. 523). We are seen by someone, somewhere, every time we make a purchase, click like on a video or social media share, swipe our points card at a store, drive past someone’s ring camera, plug in our electrical vehicle to charge, and myriad other activities too numerous to mention. This surveillance contributes to the data points that are logged for every individual.

Visibility of the people

The surveillance and visibility of all people through the algorithms that collect data should not be confused with people online being visible. Indeed, the algorithms behind many technologies serve to enforce and underscore the prejudiced paradigms often enacted in the face to face world. Huq reported that “police, courts, and parole boards across the country are turning to sophisticated algorithmic instruments to guide decisions about the where, whom, and when of law enforcement” (2019, p. 1045). This is a terrifying prospect for people of marginalized communities who have been historically targeted by the law. Alkhatib et al. summed up the findings of researchers saying “these decisions can have weighty consequences: they determine whether we’re excluded from social environments, they decide whether we should be paid for our work, they influence whether we’re sent to jail or released on bail” (2019, p. 1). The faceless anonymity afforded by the internet is not equally afforded, as the algorithms that follow us on our digital paths ensure that our life is logged and then is mathematically and computationally assessed and delivered back to us through the algorithmic governance.

Geography has historically defined the physical location of a person on the globe, however in a globalized world involving networked interactions, the definition needs to extend to the places we visit online. Researchers have argued that “space is not simply a setting, but rather it plays an active role in the construction and organization of social life which is entangled with processes of knowledge and power” (Neely & Samura, 2011; Pham & Philip, 2021). A lens of critical geography is warranted as we consider the impact and implications of the algorithmic power we engage with daily.

Although the concept of the digital divide has been a topic amongst educators since the term was first coined in the 1990s, it has by and large been limited to the concept of students having access to digital devices by which to access the information contained on the internet. The digital divide and critical geography must intersect when we examine online interactions to ascertain not only the status of the devices our students have access to, but also the subliminal reinforcers of racism, marginalization and ontological oppression embedded in the digital landscape. Gilbert argued that “‘digital divide’ research needs to be situated within a broader theory of inequality – specifically one that incorporates an analysis of place, scale, and power – in order to better understand the relations of digital and urban inequalities in the United States” (2010, p. 1001)., a statement easily extended to include Canada. The digital divide must also include the racialized experience of minorities and people of colour; insomuch as people of colour encounter advertisements online that differ from those being shown to white people, they also experience challenges such as the errors frequently made by facial-recognition systems as it has been noted that these systems “make mistakes with Black faces at far higher rates than they do with white ones” (Issar & Aneesh, 2021, p. 8). As a continent with a history of antiblackness and racism, we must be aware of “the micro and macro instances of prejudices, stereotyping, and discrimination in society directed toward persons of African descent – stems largely from how historical narratives present Black people” (King & Simmons, 2018, p. 109), not only because we have a past that facilitated racism, but because this racism is ongoing.

As an illustration of the power of the algorithm, we can look to the recent news coming out of the state of Florida. Under the current governor, Ron Desantis, the same governor who enacted the “Stop Woke Act”, and the “don’t say gay” restriction, the Black history curriculum has recently been changed to include standards that promote the racist idea that in some way slavery benefited Black people, and any discussion about the Black Lives Matter movement has been silenced in Florida schools (Burga, 2023). Upon learning of this unimaginable educational situation in Florida, I conducted a search on YouTube to try to learn more, and this search for information served to underscore Issar and Aneesh’s assertion that “one of the difficulties with algorithmic systems is that they can simultaneously be socially neutral and socially significant” (Issar & Aneesh, 2021, p. 7). My search was socially neutral when I was merely seeking more information about a current event in the state of Florida. It changed to become socially significant in the days following this quest for knowledge. What transpired after this search was a semi-bombardment of what I would categorize as racial propaganda within my device; not restricted only to my YouTube application. One brief search to learn more about a shocking topic has led to the algorithm seeking not only content that informs me as to what is occurring in Florida politics, but also providing me suggestions for content that supports what is occurring in Florida; content that I do not want to have brought to my attention repeatedly. Over time, repeated exposure to problematic or blatantly false information lends the user to begin to think that there are lots of people who believe this, and there is strength in numbers. If many people believe something to be true, it must then be true.

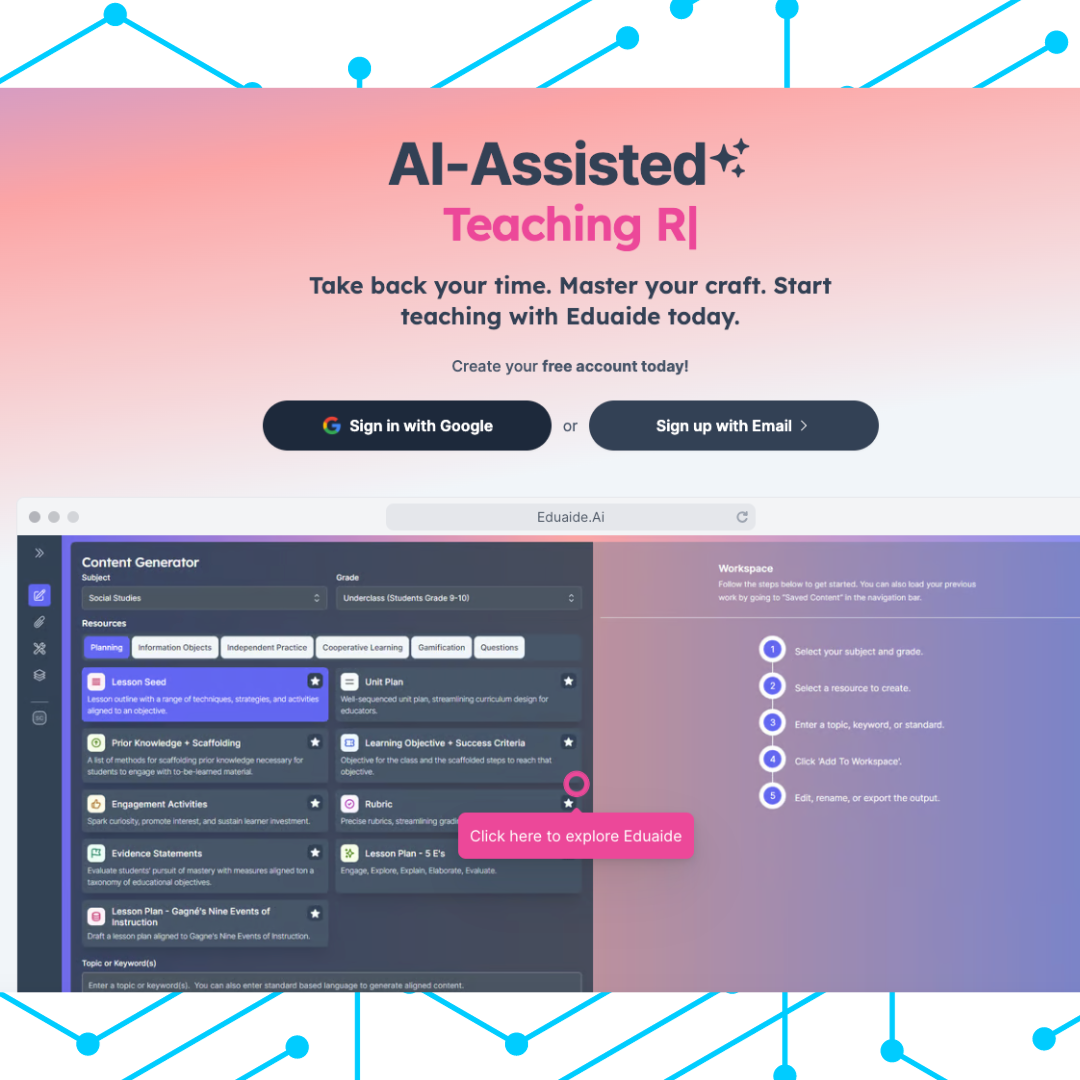

This is problematic in obvious ways, but there are also potential subtle ways that the algorithm continues to exert its power. Imagine that a teacher teaching a particular concept conducts a search to support the lesson. If the teacher has searched, for instance, something that is questionable in its factuality, something that contains racist tropes or other examples of symbolic violence, the content that this teacher will continue to be exposed to after the search will reinforce the existence of that biased and potentially harmful perspective. Further, as the teacher shares her screen before the class during instruction, there is a distinct likelihood that students will see the results of this search appearing potentially in advertisements, recommended videos in YouTube, as well as in the results of this teacher’s Google Searches. Beyond the potential for professional discomfort resulting from algorithmically suggested content, lies the epistemic problem that this content is being recycled and presented as true, realistic, informative, valuable content. In this we see what Beer warned: “power is realised in the outcomes of algorithmic processes.” (2017, p. 7). While this might produce an opportunity to teach students about algorithms and the subversive power they possess, across society algorithmic awareness is only an emergent conversation for the majority of people, implying that the teacher may not possess the language or skillset to explain the unsolicited content that is displayed on the screen during instructional time.

This is not to suggest there is no hope, and that our classrooms will be victims of algorithmic governance in the long-term. “We are now seeing a growing interest in treating algorithms as object of study” (Beer, 2017, p. 3), and with this interest will come new information for understanding, and combatting the reality of algorithmic presence. Hobbs argued that “We should know how algorithmic personalization affects preservice and practicing teachers as they search for and find online information resources for teaching and learning” (2020, p. 525). I would extend that statement to include all teachers, preservice and experienced, as algorithmic governance impacts everyone.

Conclusion

The power held by the opaque algorithms that control the flow, and the visibility of digital information presents what Rittel and Webber (1973) would call a wicked problem. Wicked problems lack the clarifying traits of simpler problems with the term wicked meaning malignant, vicious, tricky, and aggressive (p. 160). Existing with the secret phantom, the algorithm that shapes and changes our access to information is, indeed, a wicked problem. Hobbs stated that ”given the many different ways that algorithmic personalization affects peoples’ lives online, it will be important to advance theoretical concepts and develop pedagogies that deepen our understanding of algorithmic personalization’s potential impact on learning” (2020, p. 525).

Further algorithmic challenges await in the near future as we move toward a future infused with ubiquitous AI. Algorithms have brought a new type of manipulation into the digitally connected world, with the potential to further increase the polarization already being experienced in our modern society. Artificial intelligence presents a new wicked problem for education as we consider its impact on assessment, plagiarism, contract cheating and myriad other relevant topics that will reveal themselves as this new technological revolution unfolds. Educational researchers will need to continue to interrogate and explore the powers behind the algorithms that impact all digital users worldwide to advance accurate, equal, ethically responsible dissemination of information.

References

Alkhatib, A., & Bernstein, M. (2019). Street–level algorithms: A theory at the gaps between policy and decisions. Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems – Proceedings. https://doi.org/10.1145/3290605.3300760

Altay, S., Berriche, M., & Acerbi, A. (2023). Misinformation on Misinformation: Conceptual and Methodological Challenges. Social Media and Society, 9(1). https://doi.org/10.1177/20563051221150412

Aneesh, A. (2006). Virtual migration: The programming of globalization. Duke University Press.

Baker, P. (2023, August) Trump indictment, part iv: A spectacle that has become surreally routine. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/08/14/us/politics/trump-indictments-georgia-criminal-charges.html

Beer, D. (2017). The social power of algorithms. In Information Communication and Society (Vol. 20, Issue 1, pp. 1–13). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2016.1216147

Blake-Turner, C. (2020). Fake news, relevant alternatives, and the degradation of our epistemic environment. Inquiry (Oslo), ahead-of-print(ahead-of-print), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/0020174X.2020.1725623

Branelly, K. (2016). Trump campaign pays millions to overseas big data firm. NBC News. https://www.nbcnews.com/storyline/2016-election-day/trump-campaign-pays-millions-overseas-big-data-firm-n677321

Bucher, T. (2012). Want to be on the top? Algorithmic power and the threat of invisibility on Facebook. New Media & Society, 14(7), 1164–1180. https://doi-org.ezproxy.lib.ucalgary.ca/10.1177/1461444812440159

Burga, S. (2023 July). Florida approves controversial guidelines for black history curriculum. Here’s what to know. Time. https://time.com/6296413/florida-board-of-education-black-history/

Connolly, R. (2023). Datafication, Platformization, Algorithmic Governance, and Digital Sovereignty: Four Concepts You Should Teach. ACM Inroads, 14(1), 40–48. https://doi.org/10.1145/3583087

Conway, K. (2020). The art of communication in a polarized world. AU Press.

Dinesh, S. & OdabaŞ, M. (2023, July). 8 facts about americans and twitter as it rebrands to X. Pew Research. https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2023/07/26/8-facts-about-americans-and-twitter-as-it-rebrands-to-x/

Farrow, R. (2023 August). Elon Musk’s shadow rule. The New Yorker. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2023/08/28/elon-musks-shadow-rule

Foucault M (1977) Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. London: Allen Lane

Gilbert, M. (2010). Theorizing digital and urban inequalities: Critical geographies of “race”, gender and technological capital. Information, Communication & Society, 13(7), 1000–1018. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2010.499954

Harris, K. R. (2022). Real Fakes: The Epistemology of Online Misinformation. Philosophy & Technology, 35(3), 83–83. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13347-022-00581-9

Hobbs, R. (2020). Propaganda in an Age of Algorithmic Personalization: Expanding Literacy Research and Practice. Reading Research Quarterly, 55(3), 521–533. https://doi.org/10.1002/rrq.301

Huq, A. Z. (2019). Racial equity in algorithmic criminal justice. Duke Law Journal, 68(6), 1043–1134.

Issar, S., & Aneesh, A. (2022). What is algorithmic governance? Sociology Compass, 16(1). https://doi.org/10.1111/soc4.12955

Joinson, A., Houghton, D., Vasalou, A. Marder, B. (2011). Digital crowding: Privacy, self-disclosure, and technology. In Trepte, S., & Reinecke, L. (Eds.), Privacy Online (pp. 33-45). Springer Berlin Heidelberg. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-21521-6

King, L. J., & Simmons, C. (2018). 4 Narratives of Black History in Textbooks: Canada and the United States. S. A.

Neely, B., & Samura, M. (2011). Social geographies of race: connecting race and space. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 34(11), 1933–1952. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2011.559262

Norberg, P., Horne, D. R., & Horne, D. A. (2007). Privacy Paradox: Personal Information Disclosure Intentions versus Behaviors. The Journal of Consumer Affairs, 41(1), 100–126. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6606.2006.00070.x

Obar, J. A., & Oeldorf-Hirsch, A. (2020). The biggest lie on the Internet: ignoring the privacy policies and terms of service policies of social networking services. Information Communication and Society, 23(1), 128–147. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2018.1486870

Pasquale, F. (2015). The black box society : the secret algorithms that control money and information. Harvard University Press.

Pham, J., & Philip, T. (2021). Shifting education reform towards anti-racist and intersectional visions of justice: A study of pedagogies of organizing by a teacher of Color. Journal of the Learning Sciences, 30(1), 27–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508406.2020.1768098

Philip, T., & Sengupta, P. (2021). Theories of learning as theories of society: A contrapuntal approach to expanding disciplinary authenticity in computing. Journal of the Learning Sciences, 30(2), 330–349. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508406.2020.1828089

Rainie, L. & Anderson, J. (2017, May). The future of jobs and jobs training. Pew Research. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2017/05/03/the-future-of-jobs-and-jobs-training/

Rini, R. (2017). Fake news and partisan epistemology. Kennedy Institute of Ethics Journal, 27(2), E–43–E–64. https://doi.org/10.1353/ken.2017.0025

Rittel, H. W. J., & Webber, M. M. (1972). Dilemmas in a general theory of planning. Institute of Urban and Regional Development, University of California.

Shalf, J. & Leland, R. (2015). Computing beyond Moore’s Law. Computer, 48(12), 14-23. doi: 10.1109/MC.2015.374.

Translated by Content Engine, L. L. C. (2023, Feb 08). Is it the end of Moore’s Law? Artificial intelligence like ChatGPT challenges the limits of physics. CE Noticias Financieras https://ezproxy.lib.ucalgary.ca/login?qurl=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.proquest.com%2Fwire-feeds%2Fis-end-moores-law-artificial-intelligence-like%2Fdocview%2F2774910208%2Fse-2%3Faccountid%3D9838

Warzel, C. (2023, July). Elon Musk Really Broke Twitter This Time. The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2023/07/twitter-outage-elon-musk-user-restrictions/674609/