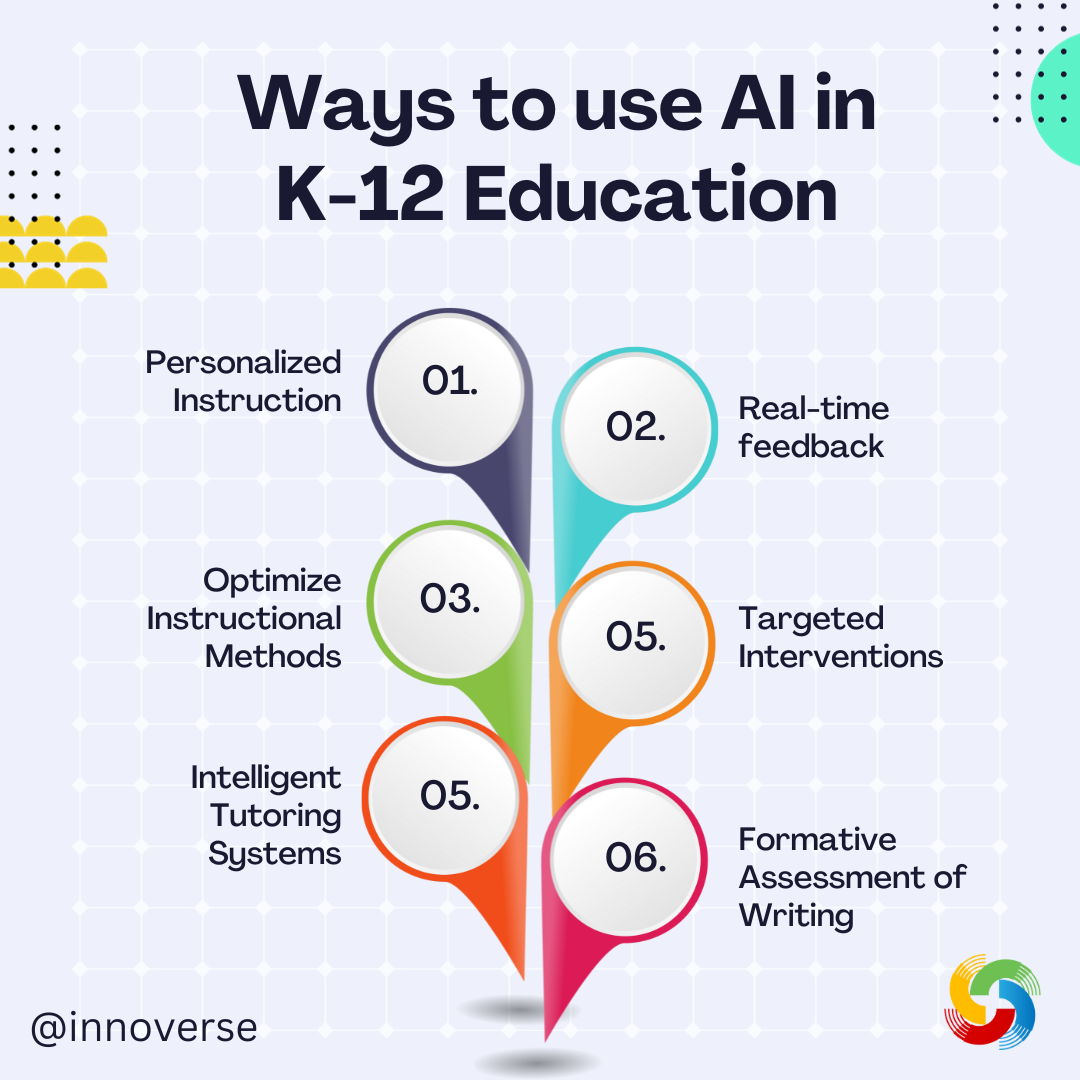

Ways to use AI in K-12 Classrooms

The empirical literature outlines a number of ways that artificial intelligence (AI) might be used in K-12 education. Despite these categories of use being identified as researchers as viable uses for AI in the K-12 classroom, many teachers are either unaware of these new resources, or they are unfamiliar with how to use these new tools, and the result is the same: at this time, they are either underutilized, or not utilized at all.

Regardless of the ubiquity (or lack thereof) of the use of these tools, we’ll briefly outline some of the potential value that the academy suggests AI may bring to the K-12 environment.

Despite a paucity of research specific to K-12 education, the literature is filled with examples of uses for artificical intelligence in the K-12 classroom. For example, Holstein et al (2018) used Lumilo as mixed-reality glasses that allowed the educator to see the physical data of the student’s body language and also provided an additional digital layer over each student (Crompton & Burke, 2022, p. 117). AI programs, such as CyWrite, WriteToLearn, and Research Writing Tutor are being used to unpack and analyze student writing and provide feedback to the educator (Hegelheimer, et al. 2016). Crompton and Burke (2022) made reference to AI tutors literature review, noting that they provide one-to-one support for students, with tutoring matched to the student’s cognitive level followed by immediate, targeted feedback (Luckin, et al. 2016). Examples of AI tutors include systems, such as ACTIVE Math, MAThia, Why2Atlas, Comet, and Viper which are used for a variety of subjects and grade levels (Chassignol et al. 2018). BERT, RoBERTa and XLNet are primarily focused on understanding the underlying meaning of text and are particularly useful for tasks such as sentiment analysis and named entity recognition (Lund & Wang, 2023, p. 27).

So, the literature is currently outlining some uses for artificial intelligence that, in my estimation, and from my vantage point of working as the coordinator of educational technology, are not yet being used by teachers who are in front of our K-12 students. We are not going to endeavour to locate and test the affordances that are mentioned in the literature, but rather, we acknowledge that there is progress made in this area on a daily basis, and as applications involving artificial intelligence become more ubiquitous and/or more affordable, their usage will be inevitable in our K-12 classrooms worldwide.

References

Chassignol M, Khoroshavin A, Klimova A, Bilyatdinova A (2018) Artificial intelligence trends in education: a narrative view. Procedia Comput Sci 136:16–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procs.2018.08.233

Crompton, H., & Burke, D. (2022). Artificial intelligence in K-12 education. SN Social Sciences, 2(7), 113. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43545-022-00425-5

Hegelheimer V, Dursun A, Li Z (2016) Automated writing evaluation in language teaching: theory, development, and application. Comput Assist Lang Instr Consort J 33(1):2056–9017

Holstein K, McLaren BM, Aleven V (2018) Student learning benefits of a mixed-reality teacher awareness tool in AI-enhanced classrooms. In: Rosé C, Martínez-Maldonado R et al (eds) Proceedings of the 19th International Conference on Artificial Intelligence in Education (AIED 2018). LNAI 10947 Springer, New York, pp 154–168

Luckin R, Holmes W, Forcier LB, Griffiths M (2016) Intelligence unleashed: an argument for AI in education. https://www.pearson.com/content/dam/corporate/global/pearson-dot-com/files/innov ation/Intelligence-Unleashed-Publication.pdf.

Lund, B. D., & Wang, T. (2023). Chatting about ChatGPT: How may AI and GPT impact academia and libraries? Library Hi Tech News, 40(3), 26–29. https://doi.org/10.1108/LHTN-01-2023-0009